Grace and Entropy

Dealing with Come-Downs and Meeting Roger Scruton; Entropy and Grace; Mary Harrington; Book of the Month: Louis Markos, From Plato to Christ; (Failing at) Gardening Update

Dealing with Come-Downs and Meeting Roger Scruton

I had to go to London and back in one day on Saturday last week. I was speaking at an event on the future of the Church in England for a group that is comprised of young professional and academic types, mostly Anglican but some Roman Catholics too. On the panel of speakers was Gavin Ashenden and Chris Moore from the Church Society. This was a lot of fun and I’m glad I did it, but, combined with the hour change on Sunday, it knocked me for six a bit. And I felt like I spent the next three or four days readjusting and recovering.

I’ve written before about the strange sense of anticlimax and comedown I have felt when I have done things in front of audiences and this time was one of the most intense. I think it is proportional to how intense the event itself is. I felt very much in the zone when I was speaking on Saturday and I really gave myself to it. But then it is as though, afterwards, I have emptied myself out and there is no energy to focus on more mundane concerns. And yet I know that I must.

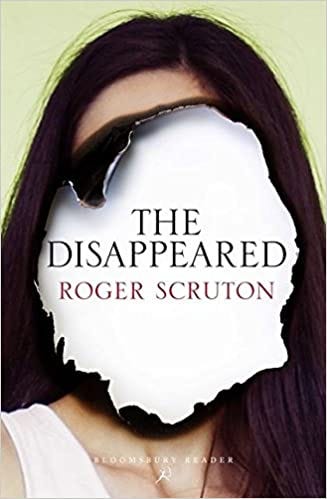

I was helped a lot by having just started Roger Scruton’s fictional book The Disappeared. I decided to buy this after finishing off another one of his books, which consists of five short stories. I started that book, Souls in Twilight, about two years ago when I was reading War and Peace. I just needed something else to read for a bit because of the intensity of the commitment. But I never finished the fifth story of Souls in Twilight. It reminded my of how much I love Roger Scruton’s thinking and writing. The Disappeared is set in a city in Yorkshire and is about the problem of multiculturalism, particularly as it applies to grooming gangs and the plight of women, both native and immigrant. It is fantastically immersive and Scruton conveys a wonderful sense of authorial empathy, neither demonising nor excusing but giving the reader what one instinctively feels is a realistic and honest assessment of the problem.

It was good for me, as I say, because I was able to lose myself in it and to feel a sense of being addressed personally by the author. It took my out of myself and my own egotistic little prison.

As I result, I rewatched a dialogue between Scruton and Jordan Peterson that I have seen already at least two or three times. This dialogue made a profound impression upon me and I do recommend it to my readers. Each of them says a number of important things, but it is Scruton’s overall vision of life, of transcendence, of the need to find things that we love and to treasure them, which I find so beautiful and inspiring.

I’d like to quote one thing in particular, which it is so essential to keep in mind, and that is about the subject of transcendence.

I think insofar as the experience of the transcendent is available to us modern people…in my own case it is the concentration on the empirical reality which at a certain point flips from mere sensory understanding to a vision in that of its communicating something to me. And I think this is what literature and art and music do at their best…they redescribe reality so that it is actually communicating something to you. It’s not just there as an inert object before you. And that sense of the transcendent is like discovering yourself in a mirror, seeing in the world as a whole that thing in you that you could never identify in words. The subject which is looking at it. And it’s not a mystery but it’s something that you can’t then explain. It’s the difference between a good writer and a bad writer…is that a good writer will describe something in such a way that the thing described has the soul of the reader in it.

Okay, so what is he talking about? He’s talking about the sense that one has that something that can’t be put into words has been communicated through an art-form or through some other experience. It might be that something of that experience can be passed on in words, but there is a sort of immediacy of address that “speaks to” you. I’m sure most people can understand this. I remember a friend of mine talking about The Lord of the Rings books, saying, “There is just so much truth in them”. And that is the kind of thing: an immediate sense that something good or true or beautiful is being communicated from one soul to another. It’s these experiences that ultimately make life worth-while. They are the moments when, as he says, the world, changes from being an inert object - something that is simply there - to something that carries meaning, something that is living and that imparts life to us.

This is what happens, I think, when we fall in love. If you’ve had that experience, you might have felt as though the rest of the world has somehow been changed by it. It is not only that the object of your love carries a certain radiancy that you are drawn to as a moth to a flame, but that, in some strange way, the rest of the world is tinged with that same mysterious and wonderful light, like the world all of a sudden possesses a glow that it didn’t have before.

The wonderful thing about culture is that it gives us a way of at least searching for a similar experience of transcendence when those exciting experiences of falling in love and discovering the world for the first time as children are no longer available to us. We can look for it in literature or in music or in poetry or painting. A lot of the time, I don’t find it and I feel depressed by my lack of success. But, when I do find it, when I find something that communicates something of truth, goodness or beauty then it is as though I am renewed within myself. And, exactly like Sir Roger says, it is a kind of wordless communication which cannot be conveyed through further information. It can be prepared for through learning and experience, but the thing itself can only be felt in its immediacy.

Watching this video again, brings back to me the sense of sadness I felt when Roger Scruton died. I had the privilege of meeting him in a seminar once when I was at King’s College London. He had a screwed up piece piece of paper in front of him on which he had scrawled about five or six words to remind him of what he had planned to talk about. His subject was aesthetics. He was such a gentleman, so learned and forceful, but kind and polite at the same time. A girl in the class who really quite a postmodern feminist took against his book which we had been given as reading. At one point, she dismissed his argument which she said purported to be objective fact but which was in fact just his opinion.

He replied in his laconic idiosyncratic fashion, “Well, yes it is my opinion. And it is up to you to tell me why I’m wrong.” And the class laughed out loud at his, as always, understated wit and candour. That was the only time I met him.

He was seventy-five when he died. He was embroiled in the scandalous attack that was made upon him by an unscrupulous philistine of a journalist who will not be named. I wish he had lived. He would have had to go through the madness of the Covid lockdowns but I would have been so interested to know how he would have responded. And he would have written more - more fiction, more philosophy. He was cut off when he was still at the height of his powers. When I read or listen to him, I feel somehow as though I am being fed or, perhaps, guided somewhere, by somebody who has seen something useful and is able to communicate it to me. That is a rare thing, in my experience. A really rare thing. And it is tragic when lights like this go out too early

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Good Things to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.